Representation in Art—A Plea for A Renaissance of Craft and Skill

Reclaiming the Natural World in Art

“In art, there is no progress, only fluctuations of intensity. Not even the greatest doctor in Bologna in the 17th century knew as much about the human body as today’s third-year medical student. But nobody alive today can draw as well as Rembrandt or Goya.”

—Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New

The contemporary environmental crisis demands more than conceptual gestures and theoretical positioning. It requires artists willing to look closely, work slowly, and master the difficult skills necessary to represent what we are losing. This essay argues for the rehabilitation of representational painting—particularly paintings of the natural environment—not as a nostalgic retreat but as an urgent contemporary practice. The tradition runs deep: from eighteenth-century theories of the sublime and picturesque to Romantic investigations of nature’s drama, and now to today’s photographers and painters documenting the devastation caused by petrochemicals. What unites this lineage is commitment to craft, to seeing clearly, to making visible the actual details of the world before us. In an art world dominated by conceptual shortcuts and theoretical posturing, the patient labor of observation and skilled rendering offers both resistance and renewal.

Landscapes in art history: The low rank that realistic portrayals of nature always had

The marginalization of landscape painting is not a recent phenomenon but an inheritance from centuries of academic hierarchy. The French Académie Royale, established in the seventeenth century, formalized what became known as the hierarchy of genres, ranking artistic subjects by their supposed intellectual and moral worth. History painting occupied the summit, depicting biblical narratives, classical mythology, and great historical events—subjects that required knowledge, imagination, and the ability to portray human psychology and action. Portraiture ranked second, genre scenes third, landscape fourth, and still life last.

This ranking was neither arbitrary nor merely aesthetic. It encoded assumptions about what deserved serious attention. The hierarchy valorized human subjects, actions, and intellect while treating the non-human world as a decorative backdrop. Landscape existed to stage human drama, not as worthy of contemplation in its own right. As late as 1669, André Félibien articulated the principle: “He who does perfect landscapes is above another who only produces fruits, flowers, or shells. He who paints living animals is more estimable than those who only represent dead things without movement. As man is the most perfect work of God on earth, it is also certain that he who becomes an imitator of God in painting human figures is much more excellent than all the others.”

The Dutch Golden Age painters of the seventeenth century challenged this hierarchy through market success, if not theoretical legitimacy. Jacob van Ruisdael, Jan van Goyen, and the Haarlem school created landscape paintings for middle-class buyers who wanted images of their land, their weather, and their distinctive light. These were not idealizations but observations that captured specific atmospheric effects and seasonal changes. Yet even this flourishing commercial market did not elevate the landscape’s theoretical status. The paintings were sold as decoration, not as exemplars of high art.

The hierarchy persisted through the academic system well into the nineteenth century. When J.M.W. Turner sought election to the Royal Academy, his landscape subjects posed problems despite his extraordinary skill. When American painters of the Hudson River School created vast panoramas of wilderness, European critics dismissed them as crude documentation rather than refined art. The hierarchy’s legacy extends into contemporary institutions: landscape paintings remain underrepresented in museum collections compared to portraits and abstraction, curators favor conceptual work addressing human subjects or the built environment over careful studies of ecosystems, and art historians continue to privilege genres that engage with human culture over those that engage with non-human nature.

This historical marginalization matters because it established intellectual frameworks that persist to this day. When contemporary critics dismiss representational landscape painting as retrograde or insufficiently critical, they echo centuries-old assumptions that the non-human world lacks the complexity and moral weight worthy of serious artistic investigation. The ecological crisis makes these assumptions untenable—and morally bankrupt, yet the institutional structures built on them remain remarkably durable.

The history of the sublime and picturesque: Romantic interests in the drama of the natural world

The eighteenth century developed two aesthetic categories that revolutionized how Western culture understood landscape and nature: the sublime and the picturesque. These concepts transformed the landscape from mere background into a subject worthy of intense philosophical and artistic attention. More importantly, they validated emotional and spiritual responses to natural phenomena that the rational Enlightenment had threatened to reduce to mechanism.

Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) distinguished between the beautiful, which produces calm pleasure through smoothness and delicacy, and the sublime, which evokes awe and even terror through vastness, obscurity, and power. Burke’s key insight was that “terror is in all cases whatsoever, either more openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.” We take paradoxical pleasure in confronting natural forces that could destroy us—towering mountains, violent storms, endless oceans—because we experience them from positions of safety. This tension between threat and security generates the sublime’s particular emotional charge.

Immanuel Kant refined Burke’s framework in his Critique of Judgment (1790), arguing that sublime experiences reveal “the superiority of our own power of reason, as a supersensible faculty, over nature.” When we confront nature’s immensity—standing before a vast glacier or beneath a starlit sky—we initially feel overwhelmed, our imagination incapable of grasping the whole. Yet this very failure demonstrates that our rational capacity exceeds what nature presents to the senses. We can think of the infinite even if we cannot see it. The sublime thus confirms human dignity through the very experiences that make us feel insignificant.

The picturesque occupied the middle ground between beauty and sublimity. William Gilpin, who coined the term in his 1782 Observations on the River Wye, argued that picturesque objects “please from some quality capable of being illustrated in painting.” The category valued roughness, irregularity, variety, and the marks of age—weathered bark, crumbling masonry, twisted vegetation. Uvedale Price’s 1794 Essay on the Picturesque identified its core qualities as sudden variation joined to irregularity, distinguishing it from beauty’s smoothness and sublimity’s terror.

Critically, the picturesque derived from pictures, specifically from seventeenth-century landscape painters Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa. Tourists seeking picturesque scenes carried Claude glasses, slightly convex, tinted mirrors that reduced three-dimensional reality to the golden atmospheric effects of Claude’s paintings. This circularity reveals something profound: aesthetic categories shape how we perceive actual landscapes. We learn to see nature through the lens of art, which, in turn, seeks to capture what we see. The picturesque demonstrated that there is no “pure” encounter with a landscape untouched by cultural mediation.

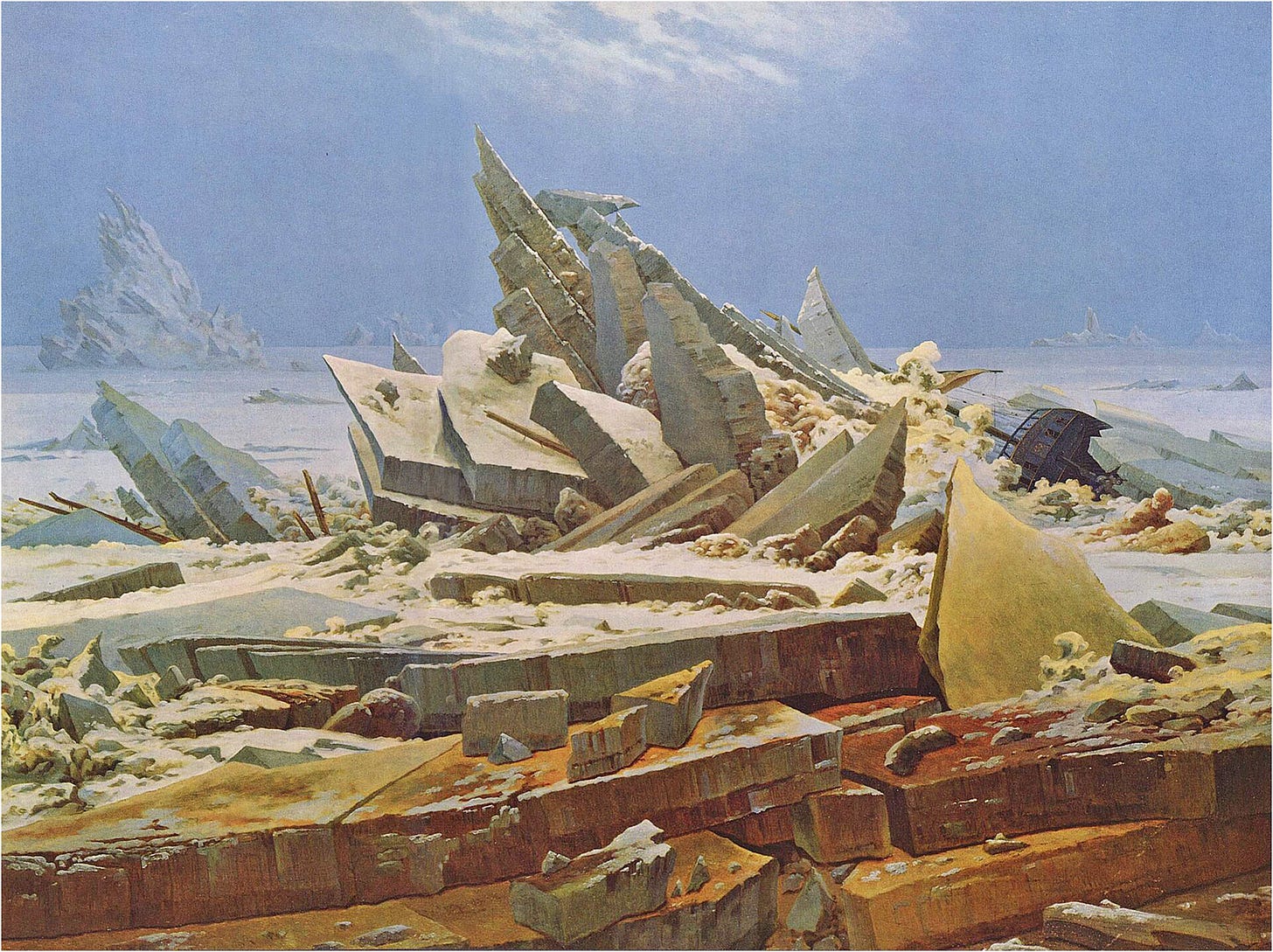

The Romantic painters translated these philosophical categories into visual form with unprecedented power. Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, such as Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, placed solitary figures before vast natural spaces, employing the Rückenfigur technique to prompt viewers to contemplate their own relationship to nature’s immensity. J.M.W. Turner painted storms, fires, avalanches, and raging seas with such atmospheric intensity that John Constable called his work “tinted steam.” These artists understood that representing overwhelming nature was not mere illustration but philosophical investigation—making visible what Burke and Kant analyzed theoretically.

The legacy of these traditions extends to contemporary practice in complex ways. The sublime helps explain our aesthetic responses to environmental devastation—the terrible beauty of petrochemical refineries at sunset, the awful grandeur of retreating glaciers. The picturesque offers a way to find aesthetic value in imperfection and decay rather than insisting on pristine wilderness. Both traditions validate sustained attention to landscape as worthy of serious artistic and intellectual engagement, countering the hierarchy that dismissed nature as merely decorative.

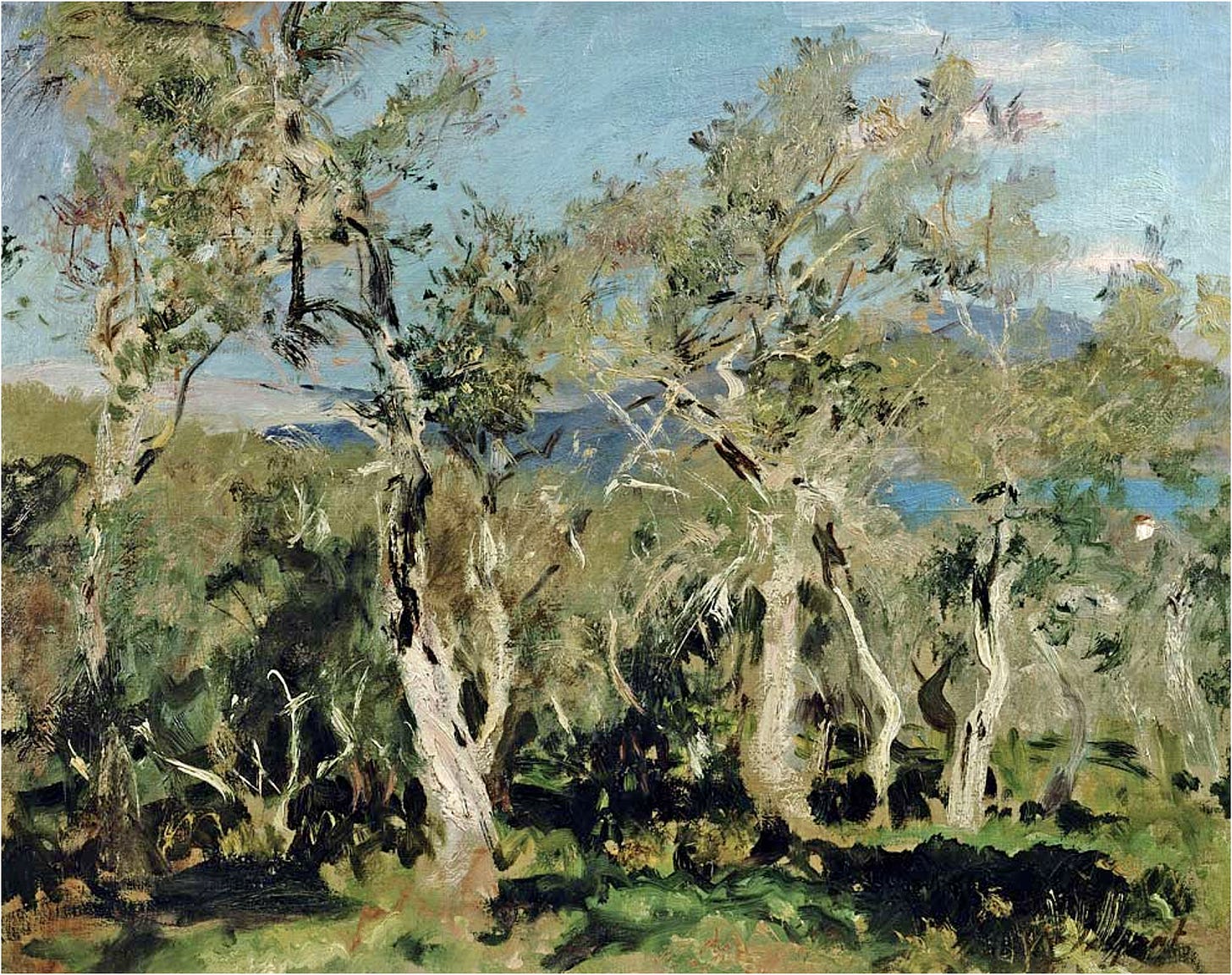

By the early decades of the nineteenth century, a quiet revolution was underway in European painting. Landscape, long consigned to the background of historical and mythological compositions, was moving to the foreground—and with it came a new insistence on direct observation of the natural world. The painters who gathered in and around the village of Barbizon, on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau south of Paris, did not set out to form a school. They were drawn together by a shared conviction that the French countryside itself—its light, its weather, its trees and fields and skies—was a subject worthy of serious artistic attention, and that the only honest way to paint it was to go outside and look.

The ground for this movement had been prepared on both sides of the English Channel. In Britain, John Constable had already demonstrated that a Suffolk meadow or a bank of summer clouds could carry the full weight of artistic ambition. His oil sketches, painted rapidly outdoors to capture transient effects of light and atmosphere, were acts of empirical inquiry as much as acts of art. When exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1824, Constable’s work struck French painters with the force of revelation. Here was a landscape rendered not from studio formulas but from sustained, almost scientific attention to what the eye actually sees.

Richard Parkes Bonington, who was born in England but lived and worked in France, served as another vital conduit between the two traditions. Bonington’s luminous watercolors and small oil studies of coastal scenes and open skies demonstrated a fluency with natural light that directly influenced French painters. His early death at twenty-five cut short a career of extraordinary promise, but his impact on the generation that followed was disproportionate to his brief years of production. Eugène Delacroix, who shared a studio with Bonington, openly acknowledged the younger painter’s gifts, and the freshness of Bonington’s technique—his willingness to let light and color do the work of description—pointed toward possibilities that the Barbizon painters would soon explore.

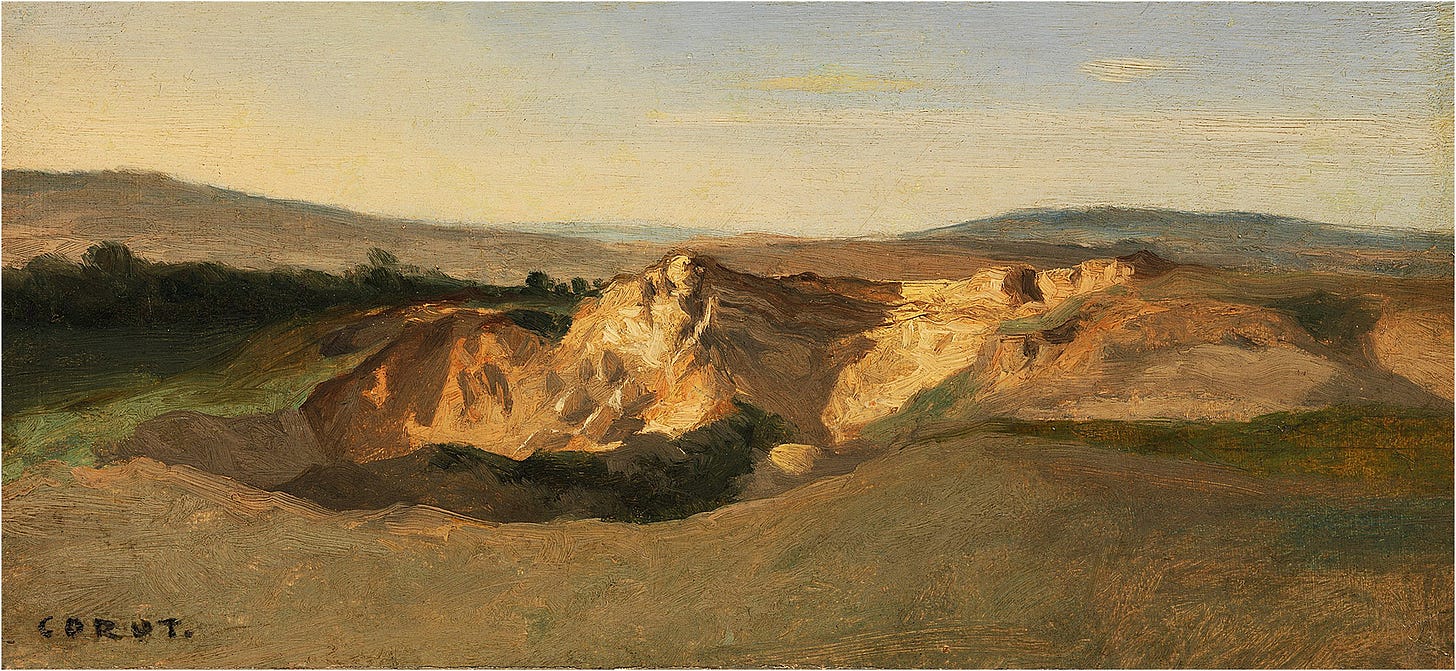

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot stands as the pivotal figure in this transition. Beginning in the 1820s with plein air studies made during his travels in Italy and later across the French countryside, Corot developed an approach to landscape that balanced classical structure with a remarkable sensitivity to atmosphere. His early Italian sketches are marvels of direct observation—silvery olive groves, sun-warmed stone, the particular quality of Mediterranean light rendered with an economy that feels almost modern. As his career matured, Corot’s landscapes grew softer and more poetic, but they never lost their foundation in careful looking. He painted what was there.

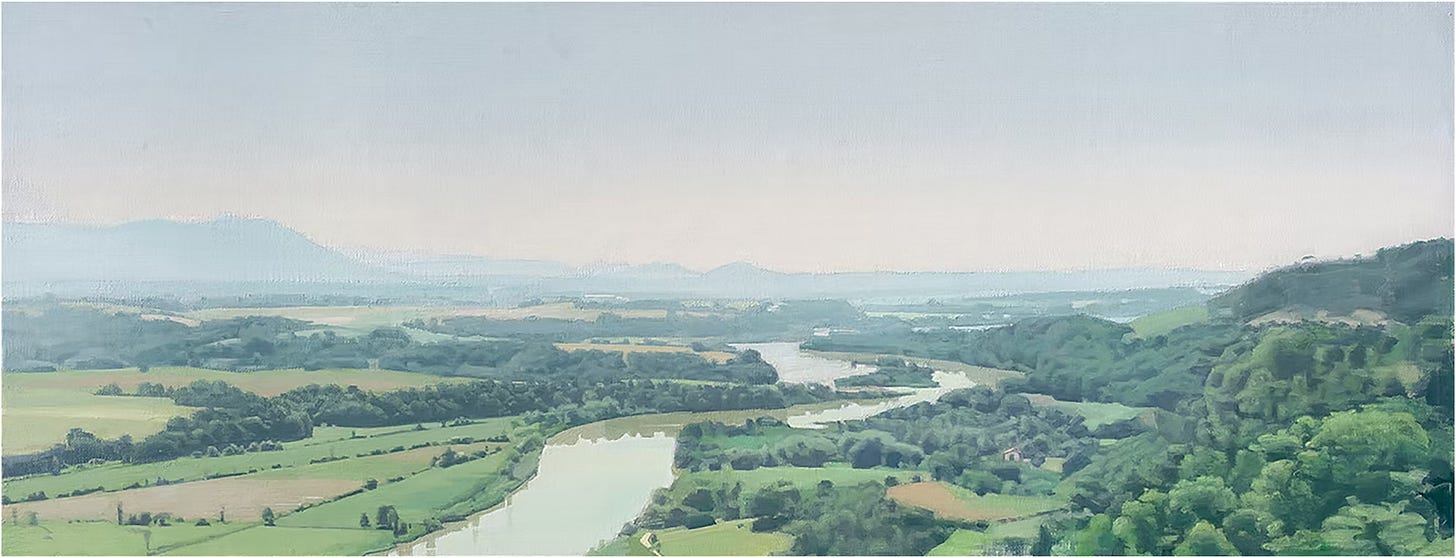

Around Corot, the Barbizon circle coalesced through the 1830s and 1840s. Théodore Rousseau devoted years to the ancient oaks of Fontainebleau, painting individual trees with a specificity that amounted to portraiture. Charles-François Daubigny worked from a floating studio on the river Oise, pursuing the most fleeting effects of water and sky. Jean-François Millet, though best known for his figures of peasant laborers, set those figures within landscapes observed with the same unflinching honesty. What united these painters was not a manifesto but a practice: they went outdoors, they looked carefully, and they painted what they found. In doing so, they laid the essential groundwork for the Impressionists who followed, and they established a principle that remains radical in its simplicity—that the natural world, observed with patience and fidelity, is enough.

Robert Hughes on craft, skill, and the limits of abstraction

Robert Hughes, who served as TIME magazine’s art critic for three decades, mounted the late twentieth century’s most sustained defense of craft and technical skill against what he saw as art education’s collapse into therapeutic validation and the art market’s elevation of conceptual gesture over hard-won ability. Hughes championed specific representational painters—Lucian Freud, foremost among them—while excoriating contemporary artists he believed couldn’t draw. His critique cut deeper than aesthetic preference: he argued that technical incompetence represented failure to confront “the very concreteness of the world.”

Hughes’s fundamental conviction was that authentic art must engage directly with physical reality. Quoting Robert Motherwell’s observation that painting is “the skin of the world,” Hughes articulated his core aesthetic: an artist’s job is to confront reality rather than to erect Platonic or utopian structures. In his 1987 essay on Lucian Freud, Hughes wrote: “There is perhaps no great work of art, abstract or figurative, without an empirical core, a sense that the mind is working on raw material that exists, out there, in the world at large, in some degree beyond mere ‘invention.’” (The Spectacle of Skill: Selected Writings of Robert Hughes, 2016).

Drawing occupied the center of Hughes’s argument about craft. He gives a vivid analogy: “An artist who can’t draw the human figure is like a poet who knows only half the alphabet: he may possess considerable passion, but he lacks the vocabulary to express it.” Drawing represented more than technical skill—it embodied a particular relationship to the world. In his 2004 Royal Academy speech, Hughes declared: “Drawing brings us into a different, a deeper and more fully experienced relation to the object. A good drawing says ‘not so fast, buster.’” The slowness matters. Drawing requires sustained attention that quick conceptual gestures bypass.

Hughes blamed the shift in art education from technical training to theoretical discourse. When art moved into universities, “theory tended to be raised above practice. Thinking deep thoughts about histories and strategies was more noble than handwork.” The ubiquity of slides and reproductions compounded the problem, “relentlessly nudging experience toward the disembodied, the conceptual, the not there.” Students learned to talk about art more than to make it, producing what Hughes called “a figurative revival partly spearheaded by the poorest generation of craftsmen in American history.”

Crucially, Hughes rejected the Greenbergian narrative that art history progresses toward abstraction. His famous formulation: “In art there is no progress, only fluctuations of intensity. Not even the greatest doctor in Bologna in the 17th century knew as much about the human body as today’s third-year medical student. But nobody alive today can draw as well as Rembrandt or Goya.” Here Hughes directly attacks the deep teleological bias inherent in much of art history and criticism. The Impressionists didn’t intend to evolve into Post-Impressionists. Art didn’t progress in a neat line toward today’s arid abstractions.

This position had profound implications. If art doesn’t progress, then working in representational modes cannot be dismissed as retrograde. Skill remains skill regardless of historical moment.

Hughes championed artists who combined traditional craft with contemporary sensibility. Thomas Eakins received his highest accolades as “the greatest realist painter America has so far produced,” praised for refusing to “tell a lie even in the service of his own imagination.” Lucian Freud exemplified what Hughes valued: “Every inch of the surface has to be won, must be argued through, bears the traces of curiosity and inquisition.” The thick impasto, the obsessive reworking, the refusal of easy effects—these testified to genuine wrestling with the massive facts of flesh and paint.

Hughes understood that abstraction could be barren and self-referential when divorced from empirical grounding. He argued that even the great modernists emerged from traditional training and maintained a connection to observed reality. Mondrian’s geometric abstractions began with the empirical beauty of his apple trees. Pollock studied with Thomas Hart Benton and painted rural landscapes before developing his drip technique. The move toward pure abstraction succeeded when it remained rooted in sensory experience; it failed when it became a mere theoretical exercise.

For landscape painting specifically, Hughes’s framework suggests that the genre’s value lies not in subject matter alone but in the quality of attention it demands. Careful observation of the patterns of shadow on snow, the way a hawk swivels its head, or the myriad color variations of green—this sustained empirical engagement represents precisely what Hughes valued. The skill required to render these observations accurately is not a decorative supplement but an embodiment of genuine knowledge. You cannot paint what you have not seen, and you cannot see without the discipline that drawing cultivates.

Elaine Scarry on Reclaiming Beauty—Especially Natural Beauty

Elaine Scarry’s On Beauty and Being Just (1999) offered perhaps the most passionate contemporary defense of beauty against decades of political suspicion and theoretical dismissal. Writing from Harvard’s Department of Aesthetics, Scarry identified a remarkable phenomenon: “For two decades or more in the humanities, various political arguments have been put forward against beauty.” These arguments claimed that beauty distracts from urgent social problems, serves as a handmaiden of privilege, and masks power relations—particularly in feminist critiques of the male gaze objectifying women’s bodies.

Scarry’s counter-argument was bold: beauty actively presses us toward justice. Our engagement with beautiful things trains habits of mind necessary for ethical life. Scarry turned political critique on its head—beauty doesn’t distract from justice; it prepares us for it.

Her phenomenological analysis of how beauty affects consciousness provides crucial resources for understanding why representational nature art matters. First, beauty “brings copies of itself into being”—it incites replication. “Wittgenstein says that when the eye sees something beautiful, the hand wants to draw it.” This impulse toward reproduction, whether through artistic creation, photography, or simply extended attention, connects aesthetic response to generative action. Drawing and painting landscapes thus express fundamental human responses to natural beauty, not arbitrary cultural practices but manifestations of how beauty works on consciousness.

Second, beauty accomplishes what Scarry calls “unselfing,” drawing on Iris Murdoch’s concept. “When we come upon beautiful things, they act like small tears in the surface of the world that pull us through to some vaster space.” Beauty decenters us from self-preoccupation: “We willingly cede our ground to the thing that stands before us.” This challenges the feminist critique of the predatory male gaze. Far from dominating through vision, the perceiver becomes vulnerable, rendered “incapacitated by love, humbled and joyful” like Dante before Beatrice.

Third, beauty demands perceptual accuracy. Beautiful things make us want to look more closely, to understand better, to get the details right. This drive toward precision carries over from aesthetic to ethical perception. If we cultivate habits of careful looking in response to beauty, those habits transfer to moral situations requiring us to perceive others accurately rather than through projections and stereotypes.

Scarry’s four attributes of beauty illuminate why natural beauty specifically matters. Beauty is sacred—it partakes of the divine, inspires reverence, and commands attention that takes us beyond mundane concerns. Beauty is unprecedented—each encounter feels singular, unlike anything else, keeping it from becoming routine. Beauty is life-saving—it pulls us back from despair, renewing engagement with existence, filling us with what Scarry calls “a surfeit of aliveness.” Beauty incites deliberation—it makes us want to understand what we’re perceiving, generating sustained investigation.

For environmental art, Scarry’s framework suggests that beautiful representations of nature serve multiple functions simultaneously. They replicate beauty, spreading attention and care rather than hoarding experience. They unself us, pulling consciousness away from anthropocentric preoccupation toward recognition of non-human value. They train perceptual accuracy, which is essential for ecological understanding. They generate life-affirming engagement rather than paralysis or despair.

Critics have questioned whether beauty truly leads to justice, noting that Nazis cultivated aesthetic refinement while committing genocide. Scarry argues that beauty makes us more attentive to fairness, not that it is automatically just. The connection is mediated, not mechanical. Yet even this more modest claim matters enormously for environmental art. If beauty cultivates the habits of attention necessary for recognizing value in non-human organisms and ecosystems, then beautiful nature paintings serve genuine ethical purposes that purely didactic or political art cannot achieve.

The contemporary crisis demands realism in all its dimensions: Richard Misrach and unsentimental truth

The synthesis of craft, beauty, and environmental engagement finds perhaps its fullest contemporary expression in Richard Misrach’s photographic practice. Since 1979, Misrach has pursued Desert Cantos, an ongoing series of over forty distinct but related bodies of work exploring the American Southwest and human intervention—floods, fires, nuclear testing, petrochemical pollution, military bombing sites, border crossings. His work demonstrates that representational art can be simultaneously beautiful and devastating, technically masterful and politically engaged, grounded in observation yet conceptually sophisticated.

Misrach’s approach navigates between what he calls “two extremes—the political and the aesthetic.” He rejects both pure documentary, which sacrifices visual power, and pure aestheticism, which ignores environmental destruction. Instead, he uses beauty as “a very powerful conveyor of difficult ideas,” creating what scholar Jennifer Peeples termed the “toxic sublime”—images that seduce viewers into contemplating sites of devastation through formal gorgeousness that initially obscures, then ultimately intensifies horror.

Petrochemical America (2012), created with landscape architect Kate Orff, exemplifies this approach. The book documents “Cancer Alley”—the 150-mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans containing over 100 petrochemical refineries and chemical plants. Misrach’s photographs capture refineries at golden hour, their towers and pipes silhouetted against spectacular sunsets, vapors catching light in ways that recall Turner’s atmospheric paintings. The images are undeniably beautiful. They are also records of one of America’s most toxic landscapes, where cancer rates far exceed national averages and predominantly poor and Black communities bear the health consequences of industrial profits.

The book’s brilliance lies in its refusal to separate beauty from truth. Orff’s ecological graphics—maps showing chemical plants, cancer clusters, fish advisories, and emission zones—provide the data that contextualizes Misrach’s photographs. Together, image and information create what they call “an Ecological Atlas,” making visible patterns that are otherwise too dispersed in space and time to perceive. Representational realism operates at multiple scales: the photographs render specific sites with documentary accuracy, while the maps reveal broader patterns of environmental injustice that no single photograph could capture.

Desert Cantos XVII: Crimes and Splendors documented dead animals—livestock, wildlife, pets—found in the desert, victims of drought, disease, vehicle strikes, and unknown causes. The photographs are starkly beautiful, the animals’ forms composed against sand and sky with the care of still life painting. But they testify to ecological violence without sentimentality or didacticism. Misrach doesn’t explain; he shows. The accumulation of images—horse carcass after coyote carcass after bird carcass—creates unbearable weight.

Bravo 20: The Bombing of the American West (1990) took a satirical approach, proposing that Nevada’s Bravo 20 military bombing range—10,000 acres cratered and contaminated—be converted into a national park with “interpretive trails” through the devastation. The photographs document what decades of Navy training exercises produced: a moonscape of craters, unexploded ordnance, shrapnel-twisted metal, and poisoned soil. Misrach printed these as large-format color photographs with the technical excellence typically reserved for wilderness landscapes, forcing viewers to confront military environmental destruction with the same careful attention usually given to natural beauty.

Border Cantos (2016), created with composer Guillermo Galindo, documented the US-Mexico border through photographs of discarded migrant belongings, border patrol infrastructure, and scarred landscapes. The images avoid sensationalism while refusing to aestheticize suffering. Galindo created musical instruments from objects Misrach photographed—water bottles, clothing, border fence materials—performing compositions that translated visual documentation into sound. The collaboration demonstrated how representational realism can extend across media while maintaining commitment to truth.

Misrach’s work proves that environmental realism need not choose between beauty and politics, craft and critique. The photographs succeed because they are technically superb—large-format clarity, sophisticated color, careful composition—while remaining grounded in specific places and ecological realities. They demonstrate craft in Hughes’s sense: sustained empirical engagement with raw material that exists “out there” rather than free-floating conceptual invention. They manifest beauty in Scarry’s sense: images that draw us into vaster spaces while making us want to look more closely. They honor the sublime and picturesque traditions while documenting what those traditions mostly ignored: not nature’s grandeur but nature’s degradation, not wilderness but wasteland, not the land before but the land after.

The case for a renaissance of skill

The argument for renewed representational landscape painting rests on converging insights from multiple traditions. The history of art’s genre hierarchy reveals that landscape’s marginalization was never merely aesthetic but ideological, reflecting anthropocentric assumptions that ecological crisis now renders untenable. The sublime and picturesque traditions demonstrate that careful attention to landscape is not decorative but philosophical, creating frameworks for understanding our relationship with nature’s power and imperfection. Robert Hughes’s defense of craft shows that technical skill embodies forms of knowledge that cannot be accessed through conceptual shortcuts. Elaine Scarry’s analysis of beauty reveals that aesthetic experience trains perceptual and ethical capacities essential for justice. Richard Misrach’s environmental photography proves that representational realism can achieve what purely abstract or conceptual work cannot: making visible the specific, located, devastating realities of ecological destruction while maintaining the formal rigor and visual power that compel sustained attention.

The renaissance this essay advocates is not a nostalgic return but an urgent contemporary practice. The environmental crisis demands artists willing to look closely at what we are losing, willing to master difficult skills necessary for accurate representation, willing to work slowly when culture accelerates, and willing to find beauty in imperfection and truth in devastation. It demands art grounded in empirical encounter with actual organisms, actual places, actual ecological relationships—not nature as abstraction or symbol but nature as the irreducibly complex, specific, vulnerable world we inhabit.

This is realism in all its dimensions: realistic in technical execution, realistic in subject matter, realistic in its unsentimental acknowledgment of destruction, realistic in its refusal to pretend that conceptual gestures substitute for sustained observation. The contemporary art world’s theoretical frameworks have created conditions in which such work is marginalized as insufficiently critical, too beautiful, too skilled, or too focused on non-human subjects. Yet the very intensity of this exclusion suggests how necessary the work is. What the art establishment cannot acknowledge, what its theories cannot accommodate, what its institutions will not validate—this may be precisely what ecological consciousness most requires.

The skills we have lost matter. The knowledge embodied in careful drawing from observation, in patient color mixing to match atmospheric effects, in compositional decisions that direct attention toward ecological relationships—these represent ways of engaging with the living world that cannot be replaced by installation, video, performance, or any other supposedly more contemporary mode. They are not inferior substitutes for conceptual sophistication but different forms of intelligence, different modes of knowledge, equally valid and arguably more urgent in a time of mass extinction.

The call, then, is for artists to reclaim what has been dismissed: the legitimacy of beauty, the value of craft, the seriousness of landscape, and the importance of representing the non-human world accurately and with care. Not because this guarantees political transformation or ensures environmental salvation, but because these practices honor what we love, document what we are losing, and cultivate the habits of attention without which we cannot hope to preserve what remains. The world needs to be seen clearly. Painting, at its best, teaches us how to see.

Other essays in this series:

Reclaiming the Natural World in Art: Some Thoughts on How We Got Here

Representation in Art—A Plea for A Renaissance of Craft and Skill